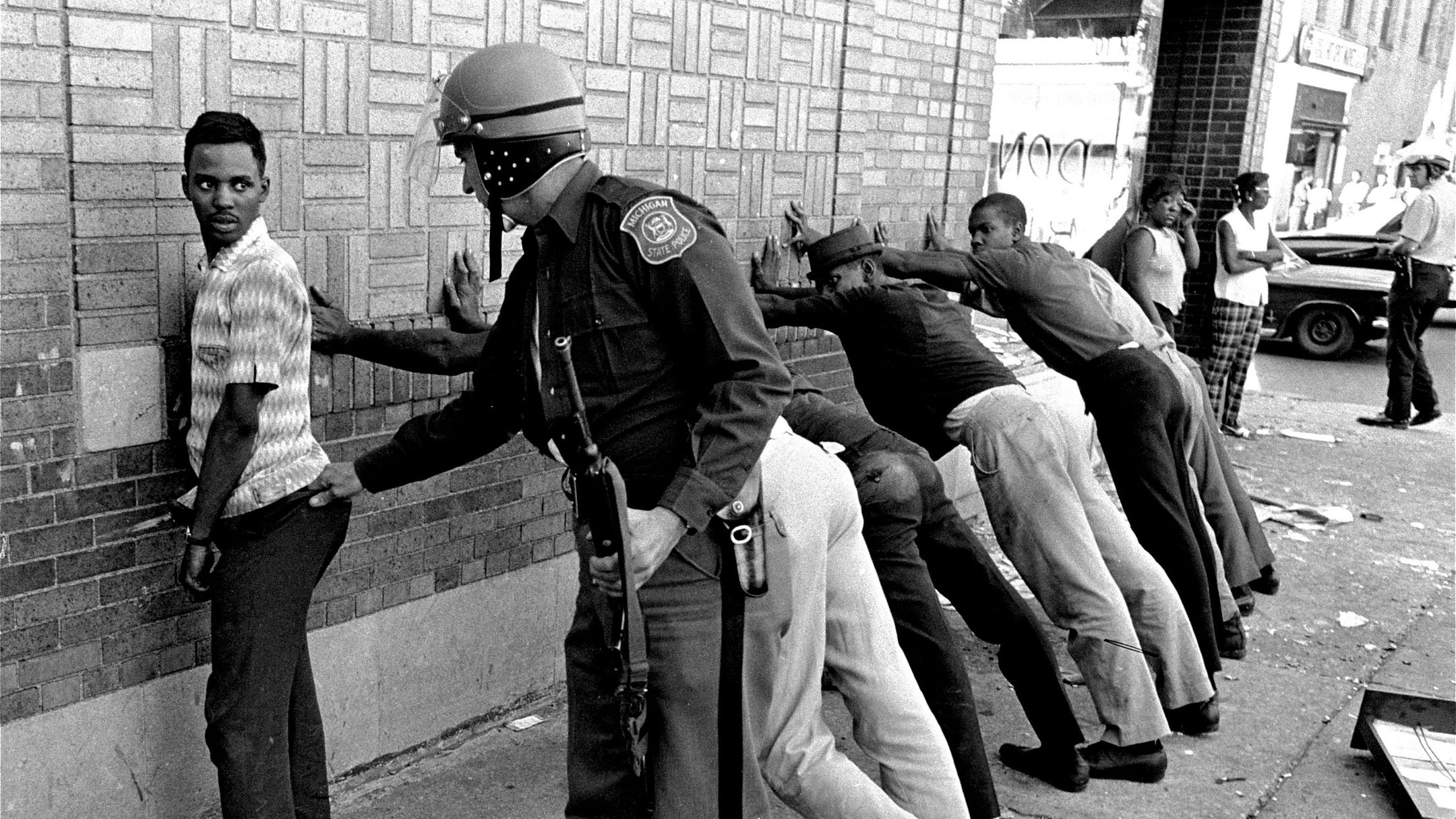

A Michigan State policeman searches a youth on Detroit's 12th Street, July 24, 1967, where looting was still in progress after yesterday's unrest. His companions lean against the wall waiting their turn. There were many arrests and at least five persons were dead. Associated Press

Two generations of Detroit activists, more than 50 years apart, converged last week at the former site of the Algiers Motel, where three Black teenagers were killed by police during the 1967 rebellion — a touchstone moment that would shape the city and community relations for decades.

“There is a straight line from the Algiers Motel to the murder of George Floyd,” longtime activist Frank Joyce told the crowd of mostly younger protesters who marched 4 miles up Woodward Avenue on Monday to the infamous spot where the motel once stood.

It was the 11th day of protests in Detroit following Floyd's death in Minneapolis under the weight of a police officer who ignored his pleas to stay alive while kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly 9 minutes.

As the summer sun lowered, the younger protesters came face-to-face with several of the city’s elders who were waiting for them at the motel site. They passed around a microphone, talking to the younger generation about the notoriously brutal — and since dismantled in the '70s — Detroit police STRESS unit and the fight for Black workers’ rights at the Dodge Main auto plant.

More: Metro Detroit marches in step with nation at racial crossroads

More: Detroit artist creates Malice Green mural

Joyce wore a Colin Kaepernick shirt, a tribute to the former NFL quarterback who set off a firestorm of protest when he took a knee during the playing of the national anthem in 2016 to protest police brutality against people of color, among other social issues. He urged the marchers to look at the big picture. Instead of "defunding the police" — one of the key demands of the current protesters — he pushed to defund the Pentagon as a means to upset the culture of militarism and violence ingrained in police departments.

"The Algiers is the perfect site to connect these historical dots," Joyce said later. "The idea of elders playing this role at this place seemed perfect to me."

Indeed, Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police, which has sparked a nationwide movement to correct systemic racism, in some ways mirrors what happened at the Algiers, where two of the victims were shotgunned at close range despite no weapons being found at the scene.

Both events have emerged as representations of the historically callous and violent treatment of African Americans by police.

Beyond the deaths of Floyd and — 53 years earlier at the Algiers— Carl Cooper, Fred Temple and Auburey Pollard, what connects the two events are the living conditions in Detroit and other urban areas. To this day, the effects of systemic racism are manifested in many of the same ways that they were in the 1960s when Joyce and the other elders marched in the streets.

Those who have marched through Detroit in the past two weeks describe an underclass living in poverty and facing deeply entrenched barriers to advancement. The city’s educational system is broken. Residents have been overtaxed hundreds of millions of dollars in property taxes. The city has shut off water service to thousands with overdue bills. High-paying jobs and decent housing for low-income individuals are scarce. A cornerstone of the city's economic development strategy involves handing out lucrative tax breaks to downtown developers, often at the expense of neighborhoods. And lingering health care disparities in the African American community tragically played out in recent months as Detroit was rocked by the coronavirus pandemic.

All of this contributes to a simmering anger among protesters and a motivation to fight for drastic change. For many, it starts with how cities are policed. Despite its long history of abuse, including 13 years of federal oversight of the department that ended in 2016, the Detroit Police Department has largely improved community relations. A sticking point, however, is that the department remains the city's highest-funded agency, by far, and police brutality and racism in the ranks remain an issue.

"As African Americans, we have been living with violence for centuries," 62-year-old Detroit resident Abayomi Azikiwe said during one of the city's recent protests. "If anyone tells us we don't have a right to be angry, that we don't have a right to take on those forces that have exploited us for centuries, then we know they are not on our side.

"We have to destroy this racist system. We can't reform it," he said.

The core issues are strikingly similar to those underpinning the anger that boiled over in 1967, elder activists at the Algiers site said. Some call the events that summer the "Detroit riot" because of the extensive property damage and violence. But many who lived through the chaos and others familiar with the city's history refer to the disturbance as a rebellion or uprising in recognition of the oppression and police brutality that Black Detroiters endured and galvanized them to react.

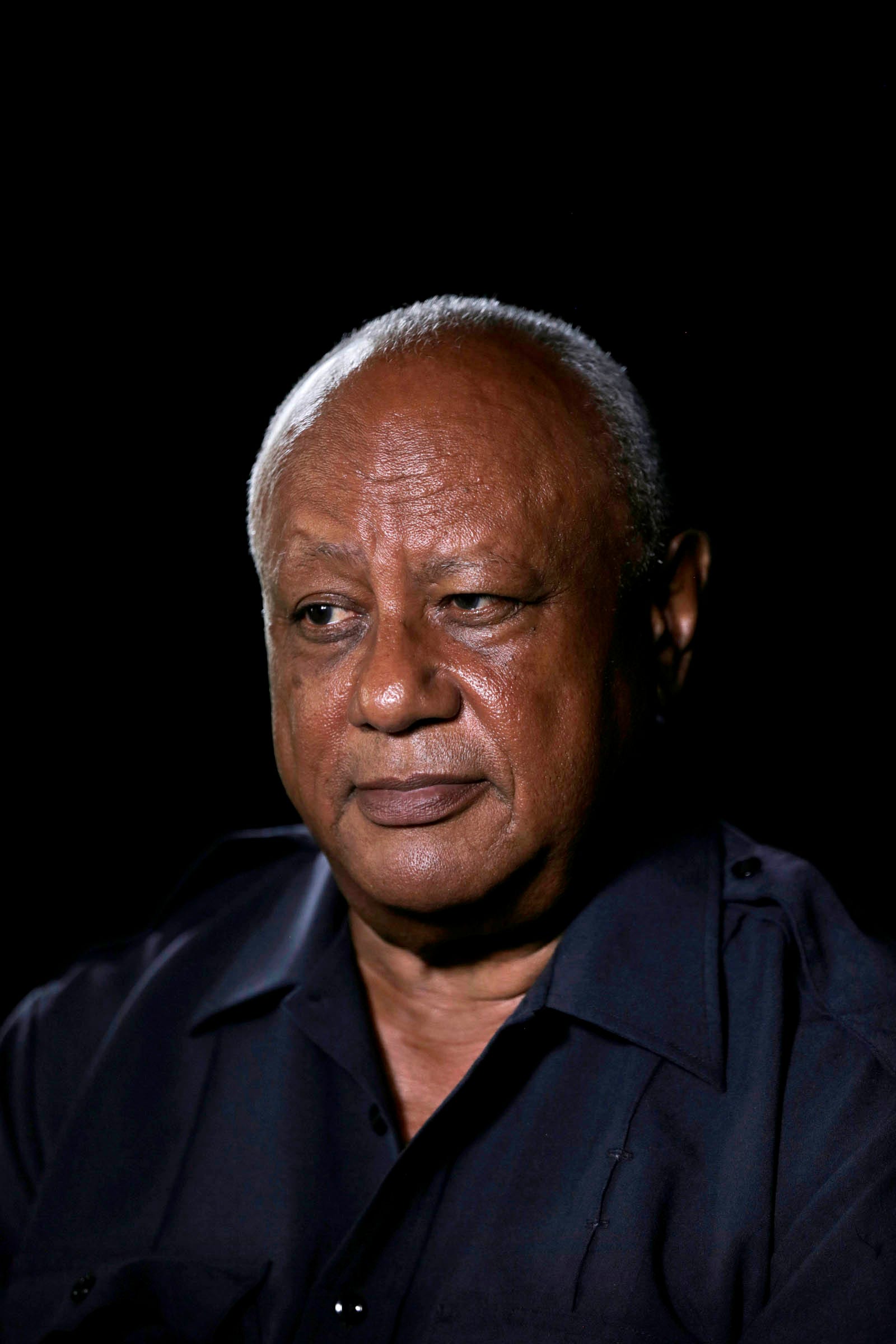

“Basically, we’re talking about the same thing,” said Dan Aldridge, 78. “Now we’re understanding the broad systemic issue of racism and its connection to other issues.”

Aldridge, who moved to Detroit from Harlem in 1965, helped convene the People’s Tribunal in August 1967 — a mock trial of sorts of the cops implicated in the killings of the three teens at the Algiers. They were found guilty, symbolically.

Monday night at the Algiers site, Aldridge recalled heavy-handed tactics by police officers that went undocumented in any public record. “This is the kind of stuff you see in foreign countries, where you can disappear,” he told the protesters.

The next day, he reflected on the meeting of the younger marchers and the activists from Detroit’s past. He wondered whether the passing of the baton was fleeting or whether it would establish a solid bridge so the two generations could organize together to abolish entrenched inequality.

“I’m all for the demonstration. I’m all for protesting,” Aldridge said. “I’m more interested in finding out, what’s the plan? What’s the objective?”

The answer likely will be a defining moment for Detroit and cities across the country.

"I am hopeful. I believe we have a more sophisticated understanding among our young people of the structural racism that our country is built on," said Joann Castle, who was involved in Detroit organizational work after the 1967 uprising and is the widow of Mike Hamlin, a prominent figure in Detroit revolutionary labor groups.

History of violence

Scenes from the first few nights of Detroit protests following Floyd’s death cemented the demonstrations as a pivotal moment in the city’s deep history of civil unrest that began long before the summer of ’67.

Police in riot gear fired cans of tear gas and shot rubber bullets at protesters. Dozens were arrested. Police Chief James Craig said the use of force was necessary because rocks and fireworks were thrown at police.

Although the violence was minimal compared with the 1967 rebellion, the clashes seemed a natural reminder of the past. At the very least, the rebellion and its causes served as lessons and inspiration to today's Detroit activists.

Tristan Taylor, one of the new movement's leaders, said at the Algiers site that the younger cohort is ready to make its own history.

"I hope it's clear now whose shoulders we stand on," he told the crowd.

It goes deeper than the uprising in 1967. Incidents sparked by racial tensions in the city include:

► The 1943 race riot, as it is known, which left 34 people dead and about 670 injured. Federal troops were called in to help deal with the violence. Historian Thomas Sugrue described the events in June 1943 as “one of the worst riots in 20th century America.”

Years of racial strife preceded the disturbance. A housing shortage led Black Detroiters to seek housing in white neighborhoods. Competition for factory jobs caused conflicts.

“The trouble began when nearly one hundred thousand Detroiters gathered on Belle Isle, Detroit’s largest park, on a hot summer Sunday. Brawls between young Blacks and whites broke out throughout the afternoon, and fights erupted on the bridge connecting Belle Isle to southeast Detroit in the evening. In the climate of racial animosity and mistrust bred by the disruptions of World War II, the brawls were but a symptom of deeper tensions. Rumors of race war galvanized whites and Blacks alike. … Many Detroit police openly sympathized with the white rioters, and were especially brutal with Blacks,” Sugrue wrote in his book, "The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit."

► The Kercheval incident, or “mini-riot,” in 1966, unfolded after police arrested a handful of activists from the Adult Community Movement for Equality (ACME) for loitering. A three-day disturbance followed that was stifled by police and community members. The city’s leadership was praised in the press for containing the incident.

► The Five-Day Rebellion in 1967 began in the early morning hours of July 23 when police raided a blind pig at 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue on Detroit’s near west side. As police loaded those inside the bar into police vans, bystanders from the neighborhood taunted the police for messing with them. Soon, bottles and bricks were being thrown. By early afternoon, the crowd swelled to 10,000 people and looting was underway.

Michigan State Police and the National Guard were called in to help. The violence spiraled out of control, with gunfire erupting throughout various neighborhoods. Guardsmen believed snipers were firing at them and would respond with gunfire. Four-year-old Tonia Blanding was shot in the chest when a Guardsman fired into her apartment at the sight of a flash believed to be a weapon. In reality, the flash likely was a match Tonia’s uncle struck to light a cigarette.

On July 26, sniper fire was reported around the Algiers Motel. Detroit and state police, along with National Guardsmen, rushed inside the motel. Although no weapon or evidence of snipers were found, Cooper, 17, Temple, 18 and Pollard, 19, were dead when authorities left.

“Several of their friends, plus two white women from Ohio, had been assaulted during a chaotic and brutal lobby interrogation,” former Free Press reporter Bill McGraw wrote in a definitive piece on the rebellion's 50th anniversary. “The killings became the most infamous episode of the week, a symbol of the uprising’s ruthlessness, especially after it was determined that two of the victims had been shotgunned at close range.”

By the uprising’s end, there were 43 dead, 1,189 injured and 7,231 arrests.

Time to organize

Although the connections to '67 are apparent, historians and activists from the '60s see the current protests as a reflection of the mid- to late-1960s in general.

Joyce, who spoke at the Algiers site, said recent events most reminded him of 1968, when more whites joined the civil rights movement following Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination.

The makeup of Detroit's protests in the last two weeks has been a much-discussed topic by the media, public officials and the protesters themselves. As the rallies stabilized into peaceful marches through the city's streets, the crowds have been consistently diverse. During the event at the Algiers, one speaker asked those from the suburbs to raise their hands. Many put an arm in the air. "Keep coming," they were encouraged.

Inkster native Lester Spence, a political science and Africana studies professor at Johns Hopkins University, drew a similar conclusion. Rather than point straight to 1967, Spence recalled the time period around King's assassination.

Spence acknowledged Detroit's persistent inequality. But rather than focus solely on comparing the city's living conditions then and now, he said he is contemplating lessons from the past so organizers can capitalize on the current momentum.

“Our challenge now is to take this moment and to make sure this moment is not like 1968 inasmuch as we really only had a two-year window, where we think, 'Oh my God, we can do everything. The world’s going to change.' And then, next thing you know, they close it up,” he said, recalling widespread cuts to social services and education in the 1970s.

Detroit's elections for city office are next year, Spence noted, and he said the current climate opens the door to electoral gains for activists to promote candidates who support their agenda.

He said the widespread support across the Detroit region — protests have popped up in Troy, Howell and other suburbs — is encouraging.

"Rather than focus on the percentage of Detroiters versus non-Detroiters, what I focus on is the beautiful thing that a significant number of people in this moment … thought it important to organize for George Floyd even though George Floyd was Black and they were not. And (secondly), they thought it important enough to cross borders even during a pandemic — really, really emphasizing that Detroit is a region, not just a city.”

The 1967 memorial

Julian Witherspoon III was 10 years old during the 1967 rebellion. He stood outside his house a few days into the uprising when he said he saw a National Guardsman shoot George Tolbert as he was moving into the neighborhood. The Guardsman said "halt" three times before firing, Witherspoon said.

“When he fired, it went through him, Mr. George Tolbert, and hit another gentleman," Witherspoon said. "They both fell at the same time. At 10 years old, I was traumatized."

Witherspoon's father — a community activist also named Julian — went to get help. Two priests from nearby St. Agnes Church helped the two wounded men into a car. Tolbert later died.

Father Norman Thomas, now 89 years old and the pastor at Sacred Heart Church near I-75 and Mack Avenue, was one of the priests who drove the men to Henry Ford Hospital.

"Fella named Julian Witherspoon came down and asked us to come up and I think it was his house on LaSalle Gardens," Thomas recalled of the scene of the shooting. "Guy was laying down on the sidewalk with a National Guard guy standing over him, next to him."

Thomas said the Guardsman took off his ID badge and didn't answer when asked who he was.

Witherspoon said the lack of police accountability remains a problem.

"Now, we’re going here, 2020, and even before 2020, with all the deaths of Black men and women who have died at the hand of police, and there’s like no prosecution just about, and no accountability," he said. "It’s basically the same game that happened back in the '60s over here in 2020.”

Witherspoon is active in the Virginia Park neighborhood. He recruited two local boys to help him tend to the 1967 rebellion's memorial near the corner of Rosa Parks Boulevard (formerly 12th Street) and Clairmount.

Together, they leveled off the dirt on memorial grave sites for those who died in 1967 and cleaned the monument bearing their names.

During a break in their work, Matthew Cole, 14, said his generation is ready to break the cycle of inequality.

"People are fed up by what’s happening. Now, instead of being a step behind it, we’re being a step ahead of it and we’re dealing with our problems today, and our generation is opening our eyes instead of just being in the dark," Matthew said. "How can we be equal if we’re steady going through stuff like that and one race is on top of another at the bottom? We need to be equals and we all gotta be on the same level.”

Joe Guillen, a member of the Free Press Investigations Team, has been covering city governance and development issues for the newspaper since 2013. He previously worked at The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer covering county and state government. Contact him at 313-222-6678 or jguillen@freepress.com.